|

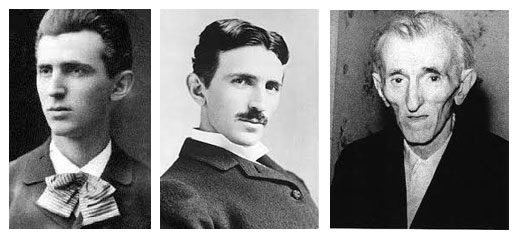

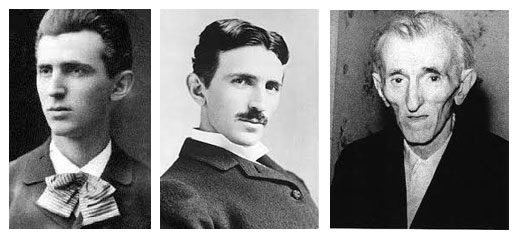

Гениальный изобретатель родился в городке Смилян — Австрийская империя, ныне в Хорватии — 10 июля 1856 г. Уже в юности Тесла выглядел демонически: высокий рост, худоба, впалые щеки, пристальный взгляд горящих глаз. Его с самого детства преследовали странные видения: вспышки невидимого для других света. Порой он на многие часы погружался в созерцание каких-то иных, неизвестных миров, таких ярких, что путал их с явью. Из этого почти сумасшествия рождались совершенно рациональные технические идеи. Особенно увлекало юношу электричество. То, что огненными зигзагами рассекало небо и сыпалось нежными искорками с шерсти обласканного кота.

О нем ходили самые разные слухи, его называли колдуном и мистификатором. Тесла ушел от официальной науки так далеко, что и сегодня большинство его работ остаются непонятыми и необъяснимыми. Ему приписывают общение с инопланетянами и даже Тунгусское явление.

Кроме занятий электротехникой, Тесла профессионально занимался лингвистикой, писал стихи. Свободно владел восемью языками (родным сербским, а также чешским, английским, французским, немецким, венгерским, итальянским и латынью), разбирался в музыке и философии.

К тому же переводил поэзию с сербского на английский, чему нашлось подтверждение:

translator tesla Еще Тесла перевел на английский поэму своего друга, известного сербского поэта Йована Йовановича (Zmaj, Jovan Jovanovic; Змей — это псевдоним) «Luka Filipov», которая затем была опубликована в ежемесячном журнале Century Magazine.

…Another anecdote about the inventor is told by the Reverend Stijacic. On his first trip to America as a young writer for the Serbian Federation, Stijacic had been surprised to find in the Chicago Public Library, a book of poems, the author of which was the popular Serbian poet, Zmaj-Jovan. The translator was Nikola Tesla. Later, when Stijacic was taken by Dr. Rado to meet the inventor in his offices on the twentieth floor of the Metropolitan Tower, he said, «Mr. Tesla, I did not know that you were interested in poetry.»

A look of wry amusement shone in the inventor’s eyes. «There are many of us Serbs who sing,» he said, «but there is nobody to listen to us.»

Adopted from «Tesla: man out of time», by Margaret Cheney, 1981.

Tesla had some interesting views on speech, language, and the dissemination of information as expressed in «The Transmission of Electrical Energy Without Wires as a Means for Furthering Peace,» Electrical World and Engineer, January 7, 1905:

Fights between individuals, as well as governments and nations, invariably result from misunderstandings in the broadest interpretation of this term. Misunderstandings are always caused by the inability of appreciating one another’s point of view. This again is due to the ignorance of those concerned, not so much in their own, as in their mutual fields. The peril of a clash is aggravated by a more or less predominant sense of combativeness, posed by every human being. To resist this inherent fighting tendency the best way is to dispel ignorance of the doings of others by a systematic spread of general knowledge. With this object in view, it is most important to aid exchange of thought and intercourse.

Mutual understanding would be immensely facilitated by the use of one universal tongue. But which shall it be, is the great question. At present it looks as if the English might be adopted as such, though it must be admitted that it is not the most suitable. Each language, of course, excels in some feature. The English lends itself to a terse, forceful expression of facts. The French is precise and finely distinctive. The Italian is probably the most melodious and easiest to learn. The Slavic tongues are very rich in sound but extremely difficult to master. The German is unequaled in the facility it offers for coining and combining words. A practical answer to that momentous question must perforce be found in times to come, for it is manifest that by adopting one common language the onward march of man would be prodigiously quickened. I do not believe that an artificial concoction, like Volapuk, will ever find universal acceptance, however time-saving it might be. That would be contrary to human nature. Languages have grown into our hearts. I rather look to the possibility of a reversion to the old Latin or Greek mother tongues, basing myself in this conclusion on the Spencerian law of rhythm. It seems unfortunate that the English-speaking nations, who are now fittest to rule the world, while endowed with extraordinary energy and practical intelligence, are singularly wanting in linguistic talent.

Next to speech we must consider permanent records of all kinds as a means for disseminating general information, or that knowledge of mutual endeavor which is chiefly conducive to harmony. Here the newspapers play by far the most important part. They are undoubtedly more effective than institutions of learning, libraries, museums and individual correspondence, all combined. The knowledge they convey is, on the whole, superficial and sometimes defective, but it is poured out in a mighty stream that reaches far and wide. Disregarding the force of electrical invention, that of journalism is the greatest in urging peace. Our schools are instrumental, mainly, in the furtherance of special thorough knowledge in our own fields, which is destructive of concordance. A world composed of crass specialists only would be perpetually at war. The diffusion of general knowledge through libraries and similar sources of information is very slow. As to individual correspondence, it is principally useful as an indispensable ingredient of the cement of commercial interest, that most powerful binding material between heterogeneous masses of humanity. It would be hard to overestimate the beneficial influence of the marvelous and precise art of photography, nor can that of other arts or means of recording be ignored. But a simple reflection will show that the peace-making force of all permanent, printed, printed or other records, resides not in themselves. It must be sought elsewhere. This is also true of speech.

I Haunted thee were the ibis nods,

From the Bracken’s crag to the Upas Tree.

Nikola Tesla, November 4, 1934

Fragments of Olympian Gossip

While listening on my cosmic phone

I caught words from the Olympus blown.

A newcomer was shown around;

That much I could guess, aided by sound.

«There’s Archimedes with his lever

Still busy on problems as ever.

Says: matter and force are transmutable

And wrong the laws you thought immutable.»

«Below, on Earth, they work at full blast

And news are coming in thick and fast.

The latest tells of a cosmic gun.

To be pelted is very poor fun.

We are wary with so much at stake,

Those beggars are a pest—no mistake.»

«Too bad, Sir Isaac, they dimmed your renown

And turned your great science upside down.

Now a long haired crank, Einstein by name,

Puts on your high teaching all the blame.

Says: matter and force are transmutable

And wrong the laws you thought immutable.»

«I am much too ignorant, my son,

For grasping schemes so finely spun.

My followers are of stronger mind

And I am content to stay behind,

Perhaps I failed, but I did my best,

These masters of mine may do the rest.

Come, Kelvin, I have finished my cup.

When is your friend Tesla coming up.»

«Oh, quoth Kelvin, he is always late,

It would be useless to remonstrate.»

Then silence—shuffle of soft slippered feet—

I knock and—the bedlam of the street.

Nikola Tesla, Novice

И хотя большинство дневников и рукописей Николы Тесла исчезли при невыясненных обстоятельствах, в Белграде существует Музей Николы Теслы, который представляет собой настоящий храм, где хранится его наследие, его личные вещи, сотни оригинальных фотографий, десятки тысяч документов, патентов, чертежей, переписка, собрания орденов, дипломов и медалей, которых он был удостоен.

Никола Тесла панически боялся микробов, постоянно мыл руки и в отелях требовал до 18 полотенец в день. Если во время обеда на стол садилась муха, заставлял официанта принести новый заказ. Поселялся в отеле только в том случае, если номер его апартаментов был кратен трём. Никола Тесла панически боялся микробов, постоянно мыл руки и в отелях требовал до 18 полотенец в день. Если во время обеда на стол садилась муха, заставлял официанта принести новый заказ. Поселялся в отеле только в том случае, если номер его апартаментов был кратен трём.

Фобии и навязчивые состояния сочетались у Теслы с поразительной энергией. Прогуливаясь по улице, он мог во внезапном порыве сделать сальто. Он часто гулял в парке и читал наизусть «Фауста» Гёте, и в эти моменты его осеняли блестящие технические идеи. С другой стороны, у него обнаруживался необъяснимый дар предвидения. Однажды, провожая друзей после вечеринки, он уговорил их не садиться в подходивший поезд и этим спас им жизнь — поезд действительно сошёл с рельсов, и многие пассажиры погибли или получили увечья.

Порой замирал и стоял долго, напряженно о чем-то думая, не замечая никого вокруг. Изобретатель сам утверждал, что мог начисто отключать свой мозг от внешнего мира.

И в этом состоянии на него нисходили «вспышки энтузиазма», «внутреннее видение» и «приступы сверхчувствительности». В эти минуты, считал ученый, сознание его проникало в загадочный тонкий мир. Резерфорд называл его «вдохновенным пророком электричества».

…Сам он уверял, что свои технические и научные откровения получал из единого информационного поля Земли.

Несмотря на то, что Тесла принял гражданство Соединенных Штатов, на своей родине, в Сербии он почитается как национальный герой. Его именем названы институты, площади, улицы по всему миру.

|